Why This is the Work

June 14-June 28, 2020

Orange County, we have a problem. The cultural inheritance of supremacy and separation is killing the planet as we know it, and killing poor people raced as Brown and Black first and worst. But here’s the good news: here in Orange County, it doesn’t take much to begin to see that many people here are also walking along pathways to resilience that follow the contours drawn from the flow of a different cultural inheritance, one fed from the much deeper well of interdependence. The good news is that tapping into that well is a wholly human act, available to any of us willing to do the work. The work required of us is to shift the white supremacist gaze to see what is actually happening here. I write to tell some stories from our work at the University of California, Irvine, to help connect some of these dots in a manner that points towards action. Through our work, we can see that the problems are connected, and so are the solutions.

I’m writing as a bi-racial cisgender woman in a multi-ethnic mixed immigrant family of economic, educational, and light skin privilege. I’m writing to appeal to people with privileges like mine who find themselves here in the Southland, looking for ways to undo racism in our own communities and to connect the dots between the pandemic and other major challenges of our time. The culture I inherited says that white and male are supreme and that humans are separate from the rest of the natural world. That’s the cultural inheritance I’m talking about. The problems may seem intractable–this pandemic or the next, the virulence of anti-Black racism, extreme social dislocation and dispossession, climate change, ecological collapse, our challenged democracy. And here in south county, for people who yearn and even work in some way to transform the effects of this cultural inheritance, it may seem disorienting to navigate this place, acting for change while being surrounded by people who are rushing to get back to business as usual. It is disorienting. Please let the following stories help you get your bearings back.

UCI students with CRECE Urban Farming Cooperative member Abel Ruiz during exchange with Visiting Artists Will See and Shammy Dee, January 2019

Story #1

Abel stepped into the church parking lot through a gap between dense corn stalks. I came to give him cardboard boxes for reuse that had been piling up at my house for months. This stop is my first errand outside of the small orbit of my family since the World Health Organization labeled the virus pandemic. In that time, the corn has grown thick and green, towering above our heads. It marks a new perimeter of the CRECE micro-farm, butting right up against the pavement. The CRECE Urban Farming Cooperative is a “Community in Resistance for Ecological and Cultural Empowerment” in Santa Ana, California, where COVID-19 infections are surging. Together with a handful of others, Abel tends the quarter acre of borrowed land, fondly referred to as la granjita, on the periphery of town. He recounted that by late March, families from across Santa Ana, feeling the pandemic’s economic pinch, started to drop by la granjita looking for land. He pointed to the plots – this family’s squash and corn along the curbside; another family’s potatoes and peas, full and thick, narrowing the garden path.

In the garden’s center circle, wide and open, a compañero tended a makeshift table top grill, wilting tomatoes, while under the oaks Esteban and Raul turned an enormous compost pile, talking about graduate school. Off in the shade, Ana, Cecelia, and two children overflowed the table with vegetables and herbs, a harvest tailored to fill the first boxes of the season. It was the first morning of the CRECE farm’s food distribution to the community. Lupe, an elder, stood by catching up as Ana prepared a box for her. We all stood physically distant with our masks on. I pulled mine down for a glance so that we could recognize one another in greeting. This was the closest I had stood to human beings outside of my family in months. I didn’t know where to put my body. There was a flow of shared labor. I leaned my pile of cardboard boxes up against the bench, touched into the flow, talked shop for a little bit, and headed back to my car where my thirteen year old waited patiently.

Abel recently joined the UC Irvine Community Resilience Projects, where I work. We cobbled together his salary from scraps of project savings and small grants. He is a Community Rebuilder, a job title we learned from exchanges fostered over the years between resident-led community efforts here in Santa Ana, California, and parallel efforts of our friends at the Menikanaehkem Community Rebuilders within the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin. As a community rebuilder, Abel is asking: what does it take to create conditions for working families of Santa Ana to have what they need to protect, defend, and nurture the biological and cultural diversity of this place? In other words, what does it take to honor and build community resilience? Right now, that question looks like: how do we feed people with dignity?

At the CRECE farm, 2019

The CRECE cooperative of urban farmers offer one response to this question. Their work also takes place in a larger context. La granjita is one thread in a growing web of similar community-driven ecological and economic justice efforts across the city of Santa Ana. Repurposing public lands, resident-led worker cooperatives, youth-led investigation of soil lead levels, protecting renters, and getting people out of confinement. On first glance, some call it ‘community development.’ Some call it ‘service.’ Some may admire the work for how it helps people bounce back from adversity. But from what I can see, this work is not about bouncing back. It is not just about meeting needs in current conditions. It is not about bootstraps or handouts. It is about bouncing forward. It is about taking a leap to honor and create the new systems, structures, and cultures we need to build healthy communities and to thrive.

At heart, these efforts tug at deep and lasting fundamental change in the purpose and workings of our economy. The projects envision a shift away from an extractive economy that harnesses a mindset of consumerism and competition in exploitative relationships to land and labor, enforced by a police state, to secure the capture and enclosure of wealth by a few. This shift away is sometimes referred to as work that aims to ‘stop the bad.’ The projects envision a shift towards honoring and building regenerative economies that harness a mindset of community and care in reciprocity- and repair-based relationships to land and labor, buttressed by deep democracy, for the purpose of achieving social justice, ecological balance, and community resilience. This shift towards is sometimes referred to as work that aims to ‘build the new.’ The Movement for Black Lives’ Policy Platform refers to such aims as “divest/invest” efforts. It is beautiful and hard work and, here in Orange County, it takes place in what the white imagination might call the margins. On the surface, it can look like work that is fueled by the philanthropic and industrial scraps of the dominant economy. It might look like the margins, but it only stays in your peripheral vision until you turn your head to look squarely at it.

Story #2

Which is what I want you to do now. Put the community circle at the center of the CRECE farm into the center of your vision. Start building out the larger story in which those tomatoes are being grilled. We are in Santa Ana, California, in early June 2020, in the COVID-19 global pandemic during what is surely to become to be known as the prolonged first wave. Santa Ana is a predominantly Latino, low-income community within the ancestral lands of the Tongva indigenous peoples and within the state-recognized county lines of Orange, which in turn occupies the ancestral lands of both the Tongva and Achjachemen peoples. Orange County has 34 cities and three million people, 12% of whom reside in places the state’s CalEnviroScreen designates as “disadvantaged communities.”

2017 Community Resilience report about equity dimension of cap-and-trade investment in Orange County

Disadvantaged communities are those living in places with the highest pollution and poverty burdens. They are places in which the state is supposed to concentrate investment in public health, quality of life, and economic opportunity. Inland Santa Ana and neighboring Anaheim are home to more than half of the state-designated disadvantaged communities in the County. They are also cities with some of the County’s most dense non-white populations. In contrast, along the Pacific Coast of Orange County, where I live on the university campus in the neighboring city of Irvine, life spreads out into sprawling upper-middle class to ultra-wealthy suburbs intermixed with some of the highest acreage of green space per capita of anywhere in southern California.

When I arrange for my house to be cleaned or my trees trimmed, Manuela and Raul travel from Santa Ana to Irvine to do the work. When I pass the recycling bin from under my desk to Maria as she makes her rounds as a service worker on our university campus, it is in Santa Ana that she has left her kids in the care of another in order to do so. When we arrange for my mother-in-law to receive in-home care in south county, those giving the care drive from places farther afield and worse off than Santa Ana and Anaheim to provide it. When, during the stay at home order, we had groceries delivered, it was Brown and Black hands, young and old, bringing the bags to my door. This summer, when families across the nation have had enough of staying in and start looking up flights to bring the kids to Disneyland, it would be our neighbors from Anaheim and Santa Ana who would be serving up the Dole Whip. Before, during, and after the pandemic, it is communities like Santa Ana and Anaheim that service upper-middle class communities like mine. Making our working life possible, then enabling us to stay at home, and starting earlier this month, servicing our fantasy of reopening ‘the economy’ in a bid to return to ‘normal.’

Story #3

As in much of the rest of the country, some of our neighbors here in Orange County are pushing to reopen as quickly as possible, and some of us who know better appear to be going along with it. Last month, to mitigate against the anticipated subsequent increased viral spread, our county medical director required people here to wear masks in public before the governor did. The most vocal people for re-opening did not want to wear masks while reopening. The reopening rhetoric here reminded me of the rhetoric following 9-11, when store owners posted window signs with an American flag depicted in the shape of a shopping bag sporting the motif, “America: Open for Business.” Now, as then, there is a veneer of bravado, a callous gesture of disregard and wishful thinking in the face of inconvenient facts, as though we are counting on the only play in the playbook that we can remember. When the going gets tough, buy something.

The county medical director stood firm and would not rescind the mask order. After a barrage of death threats, vilification, and a 24 hour protest at the home she shares with her family of three young children, the county medical director resigned. This resignation is part of a pattern playing out in public health agencies across the country. Within days of her resignation, the interim director acquiesced and lifted the mask order. Local crowds along the coast cheered it as a victory. This bravado is part of the inherited dominant culture here. And as we know, folks who are comfortable in that culture don’t want to be told to wear masks. In that spirit then, I would like us to be brave enough to pivot in order to remove a different kind of mask.

Here in Orange County, we monitor the impact of the pandemic based on numbers of reported cases, hospitalizations, and deaths tallied at the county level. Looking at the county-level numbers, until last week, it was easy to say that things didn’t look too bad. Based on those numbers, the county succeeded in its petition to Sacramento to qualify Orange County to reopen. But those numbers mask the reality of what is happening here. If there is any mask for us to remove, it is this one. Our county-level numbers looked good because in whiter and wealthy coastal communities, where people have been able to stay home, the curve is practically flat, which masks the fact that in Brown inland communities, where the people live who service the lifestyles of our coastal communities; provide the essential functions of our county; and sit in our jails and detention centers; the numbers of sick, hospitalized, and dying people are growing. They are growing rapidly and disproportionately. When unmasked, the disaggregated numbers in Orange County tell a different story, one in which it looks like Anaheim and Santa Ana emerge as COVID-19 hot spots, concentrated in zip codes of low-income communities of color. Even the disaggregated numbers don’t tell us what’s happening with our Indigenous counterparts here. If our neighbors want to unmask and reopen, let us be brave enough to demand that we together unmask this story and keep it in the center of our vision, not the periphery. If we don’t, we all pay the price.

People in Santa Ana and Anaheim who are essential and service workers are not staying home; they can’t. As more employers say that it is time to come back, more workers face the grim reality of dispossession. The dispossession that results from the decades we spent eroding the safety net and chipping away at the social contract, mechanisms that were meant to prevent people from falling through the cracks of the extractive economy in the best of times. No one said anything about what would happen during the worst of times, and yet here we are, in a time of unprecedented health and climate crisis in which the dispossession–and the role of armed state actors like police and the military in enforcing the dispossession along the lines of race–has been laid bare. The literal meaning of the word apocalypse is to uncover. To reveal. When read that way, this, indeed, is the moment we are in. This, indeed, is the work.

Let’s borrow from the climate crisis. As my colleague Hop Hopkins notes, in the climate crisis, you can’t go on with business as usual without sacrifice zones, and you can’t have sacrifice zones without disposable people, and you can’t have disposable people without racism. Fix the racism and you are on your way to fixing the climate crisis. The same logic applies here, with the pandemic. Over the past few weeks, neighborhoods across our county have joined communities across the land to come out onto the streets to defend Black life. Neighbors are talking with one another about how to move beyond the lie of white supremacy and anti-Black racism here. Ending racism here means moving beyond acceptance that some people’s lives are disposable. In the context of the pandemic, if we no longer accept the idea that some lives are disposable then it means that we also have to move beyond the idea that there will be sacrifice zones. Right now, in Orange County, that’s what we have: a plan for reopening the county that includes tacit acceptance of sacrifice zones drawn along the boundaries of race and class. Let your sight rest here for a minute. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Story #4

If we are brave enough to keep it in the center of our vision, we would see that sacrifice zones make absolutely no sense. As Anand Giridharadas reminds us, “Coronavirus makes clear what has been true all along. Your health is as safe as that of the worst-insured, worst-cared-for person in your society. It will be decided by the height of the floor, not the ceiling.” A sacrifice zone anywhere in Orange County sets the bar for public health and safety deathly low. If the waitstaff grinding pepper onto my salad is too afraid of losing her job to stay home even though she knows she’s come in contact with someone who is sick, and if there is no place for her to safely isolate anyway while juggling the needs of her family, it is not long before I will see how inextricably enmeshed my ability to navigate the protection of my own health is with the impossibility of hers. It is said that, with corona, we are in the same storm, but not the same boat. People mean for the expression to spark a sense of compassion and duty to widen the circle of care to the people in less stable boats. Here in Orange County though, it is not always the case. Here, some folks want simply to fortify further their own boat. To these neighbors, I have to ask: who’s staffing your boat? Whether the rising seas, or wildfire, or the pandemic: who’s staffing our recovery? Our fates, always linked, are now revealed as such, now more than ever. We know this interdependence to be true. The right hand would never hurt the left hand because they are part of the same body. It wouldn’t make any sense. But we’re so used to playing by the playbook of separation and supremacy that to act upon this knowledge requires an invigorating exercise of imagination.

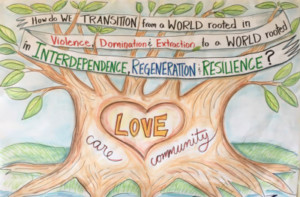

The framing question during a 2016 Transitions Lab hosted by Movement Strategy Center

Reopening Orange County without sacrifice zones allows us to rethink and reimagine our very definitions of public safety, public health, and economic vitality. If one’s own health is inextricably linked to that of the most dispossessed in society, we have a chance right now to make sure that our county’s pandemic mitigation, response, and recovery actions are aimed at protecting and fortifying the most vulnerable and disproportionately affected peoples and the places they live. The county and many of its cities have secured funds from the state and federal government to marshall action towards these ends. We don’t have to try to pretend to want to bounce back to normal. As Sonya Renee Taylor reminds us, “normal never was. Our pre-corona existence was not normal other than we normalized greed, inequity, exhaustion, depletion, extraction, disconnection, confusion, rage, hoarding, hate and lack. We should not long to return, my friends. We are being given the opportunity to stitch a new garment. One that fits all of humanity and nature.” Instead of bouncing back, the work now is to bounce forward, as CRECE and other community-driven resilience projects are showing us, into the new systems, structures, and cultures we need to transition to a just and sustainable future.

At UCI Community Resilience Projects, collaborating on such experiments is how we spend a lot of our time together outside the classroom. When Governor Newsom ordered Californians to stay home, it very quickly became clear who was left standing. The students, faculty, staff, and community collaborators who were better off financially were the ones who could continue to show up. Most everyone else was more severely gripped by the total reorganization of daily life and the need to respond rapidly to the multiple personal and community emergencies that resulted from the economic rug being pulled. Students couldn’t log in for class because they didn’t have internet connection because home away from campus was itself no longer stable. Or they couldn’t log in because they were taking care of younger siblings because their parents were sick and dying. Community collaborators nationwide turned inward for a month, reemerging fully focused on mutual aid and community defense. The race and class lines that had always been present among us were marked, indelibly. It required us to reorganize our work.

In short time, we doubled down to resource and staff the projects that aim to ’stop the bad’ and ‘build the new.’ Here in Orange County, helping CRECE open its community supported agriculture season. Nationally, bringing together the organizing team for an anticipated national training and symposium on just transition movement lawyering. And here within the University of California system, making ourselves available to the climate and environmental folks who come to us wanting to figure out how to ‘integrate diversity, equity, and inclusion’ into their work, and who leave us asking the right questions about anti-racism and systems transformation. None of these efforts would matter if we weren’t also working directly to transform what was about to happen locally in the sacrifice zones. In this doubling down, it became clear that health equity, climate equity, and racial equity had to be approached together, and that during the pandemic, we needed to pivot to build support for our county’s basic health equity infrastructure.

Story #5

In response, together with many others, we formed an Orange County Health Equity COVID-19 Community-Academic Partnership. The partnership has people with savvy from community groups and the university. In last month’s first meeting between the partnership, the Orange County Health Care Agency, and leaders from Santa Ana and Anaheim, it became clear that our hunch is correct. Folks understand that education, testing, and contact tracing are not enough. Community health workers and school district staff are standing by, ready to be trained and deployed to make sure that Santa Ana and Anaheim can lead a community-driven, robust, and informed pandemic response in this next phase that is tailored to community needs including housing, food, employment protection, and other supports that would need to be in place in order for people to be able to take care of themselves while trying to stop the spread of the virus — supports that are not right now adequately in place. Partnership participants are leading this critical work now.

As a next step along the way, partnership participants are helping UCI to design a 25-hour health equity contact tracing curriculum to be deployed over the course of one month starting late July. The curriculum will use a popular education approach to teach the basics of pandemic education and manual contact tracing with a focus on health equity, social determinants of health, community organizing, and cultural competency and humility. To support the work of community health workers, promotoras, and school districts, we envision 600 community members, resident leaders, college students, and health care agency workers with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs they need to help usher Orange County low-income communities and communities of color through this pandemic in a way the honors, taps, shifts, and builds community power for long term change. We are interested in what can become possible when we open up space for this many trained people in our communities here to tell a different story while doing the work of taking care of each other.

This is a play from a different kind of playbook. It is a play that at once draws upon ancient roots of community knowledge and is being written anew, constantly, in the streets. It is one that cooperatives like CRECE and la granjita are teaching us and our students all the time. Someone asked me recently why this is the work–why projects aimed at honoring and building community resilience are in a campus office of sustainability. This is why. We won’t get there without each other. These times uncover this truth. May we do the work that is needed to move it from the periphery to the center and act accordingly, now.

Resources

About this Note:

This note reflects perspectives of the author regarding issues related to building community resilience. It does not reflect the position of the University. Some names have been changed in the post to protect anonymity.

About the Author:

Abby Reyes is the director of UCI Community Resilience Projects. Read more.

Learn more:

OC Health Equity COVID-19 Community-Academic Partnership